Consider working more hours and taking more stimulants

Epistemic status: amphetamines

Sooner or later, the great men turn out to be all alike. They never stop working. They never lose a minute. It is very depressing.

— V.S. Pritchett

EA produces much talk about an obligation to donate some or even most of your wealth. In both direct work and earning to give, there's a connection between your work productivity and your (direct or indirect) impact. Hard work is also a costly signal of commitment that could substitute for frugality in our less funding-constrained phase of the movement. And working incredibly hard increases the chance of tail successes that might generate very high impact.

In the same way that you might want to attract converts by advancing a softer norm of donating only 10% of your income rather than everything above $40k, you might want to create a softer norm about productivity, and not feel bad about only following this norm. This post is addressed instead to those who haven't considered much at all the prospect of experimenting with working 60 hours a week rather than 30-40.

Don't dismiss this option out of hand because of general concerns about burnout. There are multiple good reasons to think you should work much harder.

First, the short-term optimal workweek might just be very long. Studies often find that CEOs work 50+ hours per week. Silicon Valley is very productive and has a "hustle culture" involving long work hours (see also). I agree with Lynette Bye that most of the working hours literature is poor—I'm even more skeptical than she is about agenda-driven research on Gilded Age factory workers—and that gaining an impression from anecdotes of top performers is better. Top performers in business routinely work long hours, and reading through lists of anecdotes like Daily Rituals (which is mostly writers and artists) you'll see a lot of strict routines, long hours, and stimulants of all kinds: caffeine, nicotine, amphetamines.

High-performing managers in the EA ecosystem report working long hours:

"I know there have been some pretty publicized debates recently in Silicon Valley about whether you can have it all and be successful and have balance, or whether you really do need to almost work yourself to death in order to accomplish something big. At least in our mind and our experience with our company is that sometimes if you want to do something that is very challenging and that you think will have a big impact and hasn’t been done before the reality is you just have to run and work harder and faster than anyone else and I think that’s a very real thing for us. We have gone all-in on this." -Theresa Condor, COO at Spire Global

"Yeah, so the limiting factor is I only want to work about 55 hours a week or something like that at the most. And so maybe I'll experiment in pushing that up to 60. But somewhere between 45 and 60 hours a week. That is hours in the office, and that transfers into Toggl hours at a rate of something like 75% to 85% just because of pee breaks and chatting to people and eating and stuff like that. And so that translates into around 40 Toggl hours, like 35 to 40 Toggl hours a week. And then, then the fraction of those that are spent on key priorities. The rest of it is meetings with people and emails, which are the two biggest sucks of time. Also internal comms, which is checking Slack or recording my goals and stuff like that." -Niel Bowerman, Director of Special Projects at 80,000 Hours

However, productive hours look more limited for certain types of cognitive or intellectual work:

"I've done several different kinds of work, and the limits were different for each. My limit for the harder types of writing or programming is about five hours a day. Whereas when I was running a startup, I could work all the time. At least for the three years I did it; if I'd kept going much longer, I'd probably have needed to take occasional vacations." -Paul Graham

"I think probably ten versus eight hours, all things considered, it's not clear they're valuable at all. Maybe, let's say the first three hours are like two thirds the value of the whole eight-hour day. And then, especially if I'm working six days a week, I'm not convinced the difference between eight and ten hours is actually adding anything in the long term." -Will MacAskill

"One way that I think about it is that the most you can increase your output from working harder is often around 25%. If you want to increase your output by 5x, or by 10x, you can't just work harder. You need to get better at skipping things, deciding what not to do, deciding what shortcuts to take." -Holden Karnofsky

So if you're interested in some kind of intellectual research (arguably a majority of 80k Hours's priority paths) then this experiment might be less worthwhile, but if you're working in operations, entrepreneurship, or community-building then it could provide valuable information about your work capacity.

Karnofsky's quote also presents the challenge that if you work normal hours, someone else can work twice as many hours as you but not three times as many. This isn't even half an order of magnitude, so you might expect work hours to be unimportant relative to working on the right problems.

This leads us to the second reason to think you should try working harder, which is that—especially early in your career—working more hours has superlinear returns because it increases the growth rate of your career. This can be true even if your short-term productivity stagnates or decreases. A good take on this: "One extremely under-rated impact of working harder is that you learn more. You have sub-linear short-term impact with increasing work hours because of things like burnout, or even just using up the best opportunities, but long-term you have super-linear impact (as long as you apply good epistemics) because you just complete more operational cycles and try more ideas about how to do the work."

A third reason is that burnout risk might be overrated if most of your impact comes from the small chance of you being a very high performer, perhaps because being 99th percentile is 100+ times better than being 90th percentile. This makes studying the habits of top performers even more useful because the survivorship bias is less important.

Addendum: stimulants

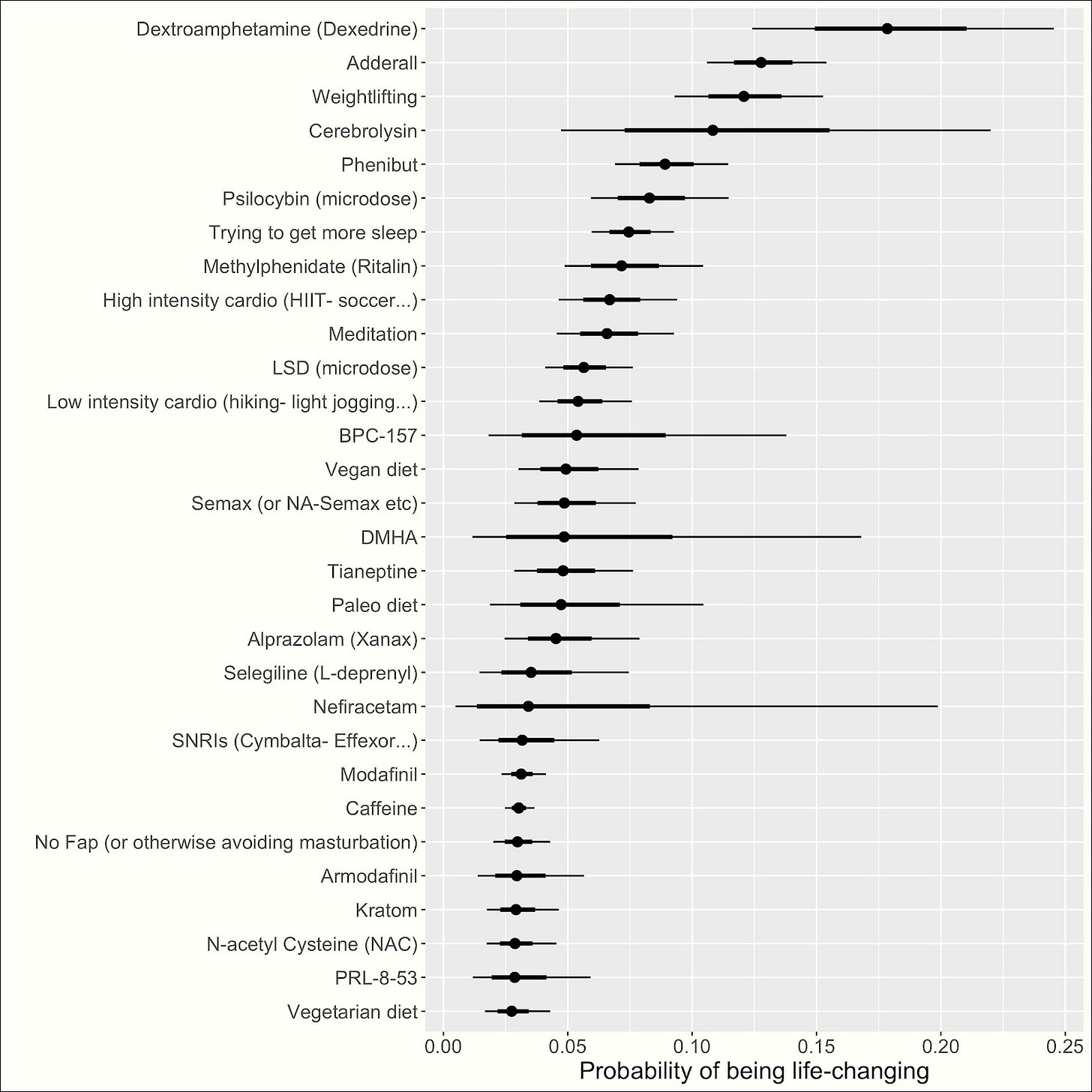

Consider this large nootropics survey and the metric "probability of life-changing effect":

Famous intellectuals, artists, and statesmen throughout history often took stimulants, sometimes in copious amounts. Silicon Valley culture has a similar reputation. Besides lifestyle interventions like lifting weights (12% chance of a life-changing effect), sleeping more, and running, there could be huge information value from experimenting with modafinil or amphetamines like Adderall (12.5% chance) just from a modest probability of a life-changing effect. If your AI timelines are long enough, you should consider long-term health effects: Scott Alexander wrote in 2017 that Adderall risks resemble “the risks of eating one extra strip of bacon per day.”

But do stimulants work in the long-run? From what I’ve seen in people with ADHD (admittedly not the best population to use as a benchmark), stimulants have significant effects for people over the course of 1 - 3 years, but over a long enough period the stimulants drop off considerably in their effectiveness. Worse, long term use can leave these people struggling quite a while after they stop using them (ie, they don’t just drop to their pre-stimulant baseline), so just stopping because the benefits have petered out may not be an option.

And this is all assuming that stimulants work well as nootropics for people without deficits like ADHD. I’ve seen evidence that modafinil has performance-enhancing effects for most people (though perhaps with some negative side effects like tunnel vision, which may not be helpful when you need to be creative or flexible), but it’s not at all clear that Adderall or Ritalin work very well for neurotypicals.

Sure, if you can find meaningful, useful work.